NFAs

31 Jan 11:30 AM

CSCI 5100

Sketch

- NFAs

- Motivation

- Formal Definition

- Conversion to DFAs

Motivation

Closure under \(\cdot\)

\[ M_1 = (Q_1, \Sigma, \delta_1, q_1, F_1) \land M_2 = (Q_2, \Sigma, \delta_2, q_2, F_2) \implies \]

\[ \exists M_3 : L(M_3) = L(M_1) \cdot L(M_2) = L(M_1)L(M_2) = A_1A_2 \]

Non-trivial

- A natural strategy

- Take \(M_1\)

- Connect states in \(F_1\) (\(M_1\) accept)

- Add edges out of \(F_1\)

- Connect edges to \(q_2\) (\(M_2\) start)

Problem

- How do we know if we should go to \(M_2\) at a given time.

- Suppose \(M_1\) requires

0appear in odd-length substrings \(\{0\}^{2n+1}\). - Suppose \(M_2\) requires

0appear in even-length substrings \(\{0\}^{2n}\). - Imagine seeing a

0after a1 - Do you leave \(M_1\) into \(M_2\) or not?

- Suppose \(M_1\) requires

- Simply do both.

Nondeterminism

Deterministic Finite Automata (DFA)

Nondeterministic Finite Automata (NFA)

New Features

- In DFAs, the \(\cap\) of any pair of labels on outgoing edges must \(=\varnothing\).

- Labels appear exactly once.

- NFAs - no such restriction.

- In NFAs, we can use \(\sigma\) to move regardless of input.

- If NFAs, accept if any path reaches any accepting state.

- That is, there may be multiple paths.

Exercise 0

Find a string accepted by the NFA that is rejected by the DFA.

Solution 0

Exercise 1

- Define an expression over \(\delta\) that holds if a finite automata is deterministic.

- You may write it in formal mathematics or in Python.

Solution 1

- We note that Python dictionaries can only be used for the \(\delta\) of a DFA.

- To implement an NFA, what would we do?

Aside

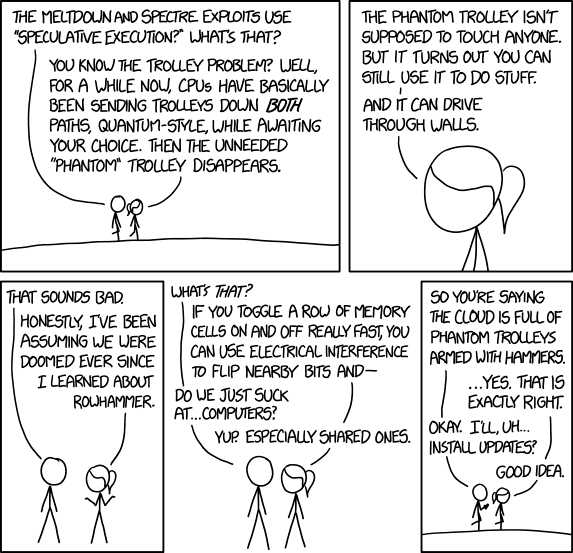

- Historically, nondeterminism not regarded as an actually physical existing device.

- In practice, speculative execution is exactly that.

- My automata research applied nondeterminism to x86-64 processors.

- Cloud computing, today, is quite similar.

Speculation

3 ways:

Computational: Fork new parallel thread and accept if any thread leads to an accept state.

Mathematical: Tree with branches. Accept if any branch leads to an accept state.

Magical: Guess at each nondeterministic step which way to go. Machine always makes the right guess that leads to accepting, if possible.

\(\delta\)

- Versus DFAs, NFAs are unaltered except in \(\delta\)

- DFAs consider individual state and a letter.

- NFA \(\delta\) most work over sets of states.

Step 0

- Alter \(\delta\)’s codomain (set of destination)

- DFA : \(\delta : Q \times \sigma \rightarrow Q\)

- NFA : \(\delta : Q \times \sigma \rightarrow \mathcal{P} (Q)\)

- \(\mathcal{P} (Q)\) is the power set of \(Q\)

- \(\mathcal{P} (Q) = \{ R | R \subset Q \}\)

In Python

Step 1

- Alter \(\delta\)’s domain (set of inputs)

- DFA : \(\delta : Q \times \sigma \rightarrow Q\)

- NFA: \(\delta : \mathcal{P} (Q) \times \sigma \rightarrow \mathcal{P} (Q)\)

- In Python, this is simple set comprehension of the Step 0 \(\delta\)

In Python

# setup

state : str

letter : str

dfa : tuple

nfa : tuple

def q_next_dfa(m:dfa, q:state, a:letter) -> state:

d = m[2] # dict of state:dict of letter:state

return d[q][a]

def q_next_nfa(m:nfa, qs:set, a:letter) -> set:

d = m[2] # dict of state:dict of letter:set of state

return {q_n for q in d[q][a] for q in qs}- Can do this with

lambda(which I’d prefer) but then we lose type hints.

Lambda

Or put the lambdas in the *FA

Conversion

Goal

- Wish to show any NFA language can be recognized by a DFA.

- Take an NFA

- \(M = (Q, \Sigma, \delta, q_0, F)\)

- Construct a DFA

- \(M = (Q', \Sigma, \delta', q'_0, F')\)

- We use the same insight as with \(\delta\)

DFA States

- Let \(Q' = \mathcal{P} (Q)\)

- One deterministic state for all possible combinations

- How many is this?

- How can we represent it?

- We note \(\Sigma\) is unaltered.

DFA \(\delta'\)

- We note \(\Sigma\) is unaltered.

- We note NFA \(\delta\):

- Accepts \(\mathcal{P} (Q)\) and a letter

- Produces \(\mathcal{P} (Q)\)

- That the states \(Q'\) of the DFA are \(\mathcal{P} (Q)\)

- \(\delta\) = \(\delta'\)

DFA \(F\)

- The DFA tracks a set of possible states.

- Only one state need be accepting.

- \(F' = \{ R \in \mathcal{P} (Q) | R \cap F \neq \varnothing \}\)

Theorem 2

\[ \forall M_{NFA}: \exists M_{DFA} : L(M_{NFA})) = L(M_{DFA})) \]

Proof

\[ \begin{aligned} M_{NFA}(&Q, \Sigma, \delta, q_1, F_1) = \\ M_{DFA}(&\mathcal{P} (Q), \Sigma, \delta, \{q_1\}, \\ & \{ R \in \mathcal{P} (Q) | R \cap F \neq \varnothing \})\blacksquare \end{aligned} \]

- We take some minor liberties with precisely defining the type of \(\delta\).