Sklearn

Scientific Computing

Why Sklearn?

What is Sklearn?

Sklearnorscikit-learn, originally conceived as an extension to SciPy.

Why sklearn?

- “Simple and efficient tools for predictive data analysis”

- “Accessible to everybody, and reusable in various contexts”

- “Built on NumPy, SciPy, and matplotlib”

- “Open source, commercially usable - BSD license”

Why not sklearn?

- The closest thing to competitors, to my knowledge, are Torch and Tensorflow.

- The Meta and Google GPU-accelerated frameworks, respectively.

- I don’t like that the other frameworks are managed by big tech companies, and I don’t think they are as well suited to science.

Using Sklearn

- Sklearn/scikit-learn is incrementally more involved to install via

pipbecause, well, sometimes it is called “sklearn” and sometimes “scikit-learn”. - This gets me almost every time:

$ python3 -m pip install sklearn

Collecting sklearn

Downloading sklearn-0.0.post12.tar.gz (2.6 kB)

Preparing metadata (setup.py) ... error

error: subprocess-exited-with-error

× python setup.py egg_info did not run successfully.

│ exit code: 1

╰─> [15 lines of output]

The 'sklearn' PyPI package is deprecated, use 'scikit-learn'

rather than 'sklearn' for pip commands.Use scikit-learn

- Scikit-learn recommends the following:

python3 -m pip install scikit-learn

python3 -m pip show scikit-learn # show scikit-learn version and location

python3 -m pip freeze # show all installed packages in the environment

python3 -c "import sklearn; sklearn.show_versions()"- You will see a lot of text.

Easier

- Just open

python/python3and

- Like SciPy, usually parts of Sklearn are imported, so that isn’t an expected two-letter name like

nporpd - I never use sklearn without at least pandas, NumPy, and Matplotlib.

These Slides

- We will focus on cognitive and vision science, motivated by the legendary example that drove early machine learning research…

THE MNIST DATABASE

of handwritten digits

Citation

mnist.bib

@article{lecun1998mnist,

title={The MNIST database of handwritten digits},

author={LeCun, Yann},

journal={http://yann. lecun. com/exdb/mnist/},

year={1998}

}Credit

- I will follow this guide:

- Recognizing hand-written digits

The Data

- The MNIST dataset is pretty easy to find, even if the original source isn’t maintained anymore.

- In fairness, it was posted before I started kindergarten

- German for “children garden”

- It is so much everywhere, it is built into sklearn!

Look at it

{'data': array([[ 0., 0., 5., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 0., ..., 10., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 0., ..., 16., 9., 0.],

...,

[ 0., 0., 1., ..., 6., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 2., ..., 12., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 10., ..., 12., 1., 0.]]),

'target': array([0, 1, 2, ..., 8, 9, 8]),

'frame': None,

'feature_names': ['pixel_0_0',

'pixel_0_1',

'pixel_0_2',

'pixel_0_3',

'pixel_0_4',

'pixel_0_5',

'pixel_0_6',

'pixel_0_7',

'pixel_1_0',

'pixel_1_1',

'pixel_1_2',

'pixel_1_3',

'pixel_1_4',

'pixel_1_5',

'pixel_1_6',

'pixel_1_7',

'pixel_2_0',

'pixel_2_1',

'pixel_2_2',

'pixel_2_3',

'pixel_2_4',

'pixel_2_5',

'pixel_2_6',

'pixel_2_7',

'pixel_3_0',

'pixel_3_1',

'pixel_3_2',

'pixel_3_3',

'pixel_3_4',

'pixel_3_5',

'pixel_3_6',

'pixel_3_7',

'pixel_4_0',

'pixel_4_1',

'pixel_4_2',

'pixel_4_3',

'pixel_4_4',

'pixel_4_5',

'pixel_4_6',

'pixel_4_7',

'pixel_5_0',

'pixel_5_1',

'pixel_5_2',

'pixel_5_3',

'pixel_5_4',

'pixel_5_5',

'pixel_5_6',

'pixel_5_7',

'pixel_6_0',

'pixel_6_1',

'pixel_6_2',

'pixel_6_3',

'pixel_6_4',

'pixel_6_5',

'pixel_6_6',

'pixel_6_7',

'pixel_7_0',

'pixel_7_1',

'pixel_7_2',

'pixel_7_3',

'pixel_7_4',

'pixel_7_5',

'pixel_7_6',

'pixel_7_7'],

'target_names': array([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]),

'images': array([[[ 0., 0., 5., ..., 1., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 13., ..., 15., 5., 0.],

[ 0., 3., 15., ..., 11., 8., 0.],

...,

[ 0., 4., 11., ..., 12., 7., 0.],

[ 0., 2., 14., ..., 12., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 6., ..., 0., 0., 0.]],

[[ 0., 0., 0., ..., 5., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 0., ..., 9., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 3., ..., 6., 0., 0.],

...,

[ 0., 0., 1., ..., 6., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 1., ..., 6., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 0., ..., 10., 0., 0.]],

[[ 0., 0., 0., ..., 12., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 3., ..., 14., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 8., ..., 16., 0., 0.],

...,

[ 0., 9., 16., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 3., 13., ..., 11., 5., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 0., ..., 16., 9., 0.]],

...,

[[ 0., 0., 1., ..., 1., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 13., ..., 2., 1., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 16., ..., 16., 5., 0.],

...,

[ 0., 0., 16., ..., 15., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 15., ..., 16., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 2., ..., 6., 0., 0.]],

[[ 0., 0., 2., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 14., ..., 15., 1., 0.],

[ 0., 4., 16., ..., 16., 7., 0.],

...,

[ 0., 0., 0., ..., 16., 2., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 4., ..., 16., 2., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 5., ..., 12., 0., 0.]],

[[ 0., 0., 10., ..., 1., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 2., 16., ..., 1., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 15., ..., 15., 0., 0.],

...,

[ 0., 4., 16., ..., 16., 6., 0.],

[ 0., 8., 16., ..., 16., 8., 0.],

[ 0., 1., 8., ..., 12., 1., 0.]]]),

'DESCR': ".. _digits_dataset:\n\nOptical recognition of handwritten digits dataset\n--------------------------------------------------\n\n**Data Set Characteristics:**\n\n:Number of Instances: 1797\n:Number of Attributes: 64\n:Attribute Information: 8x8 image of integer pixels in the range 0..16.\n:Missing Attribute Values: None\n:Creator: E. Alpaydin (alpaydin '@' boun.edu.tr)\n:Date: July; 1998\n\nThis is a copy of the test set of the UCI ML hand-written digits datasets\nhttps://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Optical+Recognition+of+Handwritten+Digits\n\nThe data set contains images of hand-written digits: 10 classes where\neach class refers to a digit.\n\nPreprocessing programs made available by NIST were used to extract\nnormalized bitmaps of handwritten digits from a preprinted form. From a\ntotal of 43 people, 30 contributed to the training set and different 13\nto the test set. 32x32 bitmaps are divided into nonoverlapping blocks of\n4x4 and the number of on pixels are counted in each block. This generates\nan input matrix of 8x8 where each element is an integer in the range\n0..16. This reduces dimensionality and gives invariance to small\ndistortions.\n\nFor info on NIST preprocessing routines, see M. D. Garris, J. L. Blue, G.\nT. Candela, D. L. Dimmick, J. Geist, P. J. Grother, S. A. Janet, and C.\nL. Wilson, NIST Form-Based Handprint Recognition System, NISTIR 5469,\n1994.\n\n.. dropdown:: References\n\n - C. Kaynak (1995) Methods of Combining Multiple Classifiers and Their\n Applications to Handwritten Digit Recognition, MSc Thesis, Institute of\n Graduate Studies in Science and Engineering, Bogazici University.\n - E. Alpaydin, C. Kaynak (1998) Cascading Classifiers, Kybernetika.\n - Ken Tang and Ponnuthurai N. Suganthan and Xi Yao and A. Kai Qin.\n Linear dimensionalityreduction using relevance weighted LDA. School of\n Electrical and Electronic Engineering Nanyang Technological University.\n 2005.\n - Claudio Gentile. A New Approximate Maximal Margin Classification\n Algorithm. NIPS. 2000.\n"}Okay

digitsis a “bunch”, which I’d never actually heard of before in my life, but appears almost identical to a Pythondictor “dictionary.

- Here’s a

dict

Dictionaries

What is a Dictionary?

- A dictionary is a built-in Python data type used to store collections of data.

- It stores data in “key-value” pairs.

- Dictionaries are unordered, mutable (like lists, not like tuples), and indexed by keys.

Key-Value Storage

- Each item in a dictionary consists of a key and its corresponding value.

- Keys must be unique and immutable (e.g., strings, numbers, tuples).

- Cannot be lists!

- Values can be of any data type and can be duplicated.

Why dictionaries?

- Think of a physical dictionary: a “key” (the word) points to a “value” (its definition).

- Python dictionaries work similarly, storing unique keys that retrieve associated values.

- This structure is powerful for organizing data where each piece needs a distinct label.

Accessing Values

- Values are accessed by referring to their associated key.

- You can use square brackets

[]or the.get()method. .get()returnsNoneor a default value if the key is not found, preventing errors.

Adding and Updating Items

- New key-value pairs can be added by assigning a value to a new key.

- Existing values can be updated by assigning a new value to an existing key.

Deleting Items

- Items can be removed using the

delkeyword or the.pop()method. .pop()also returns the value of the removed item.

- Also check

my_dict:

NumPy Arrays

- While

np.ndarrayis a homogeneous data structure, dictionaries can store heterogeneous data. - Dictionaries can be used to organize parameters or metadata associated with NumPy arrays.

pandas DataFrames

- Dictionaries are commonly used to create

pd.DataFrameobjects. - Keys become column names, and values (lists or arrays) become column data.

- This provides a natural way to structure tabular data before DataFrame creation.

DataFrame Column Selection

- Dictionaries can be used to map original column names to new, more descriptive names.

- This is useful for renaming columns in a

pd.DataFrame.

In sklearn

- Dictionaries are fundamental for defining model parameters (hyperparameters) in

sklearn. - They are used in

GridSearchCVorRandomizedSearchCVto specify parameter grids for tuning.

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

params = {"penalty": "l1", "C": 0.1, "solver": "liblinear"}

model = LogisticRegression(**params)

model.get_params(){'C': 0.1,

'class_weight': None,

'dual': False,

'fit_intercept': True,

'intercept_scaling': 1,

'l1_ratio': None,

'max_iter': 100,

'multi_class': 'deprecated',

'n_jobs': None,

'penalty': 'l1',

'random_state': None,

'solver': 'liblinear',

'tol': 0.0001,

'verbose': 0,

'warm_start': False}Model Configuration

- Dictionaries can store various configuration settings for an

sklearnpipeline or model. - This makes configurations easily readable, modifiable, and transportable.

Aside: f-Strings (Format Strings)

- f-strings offer a concise and readable way to embed Python expressions inside string literals.

- They are prefixed with an

f(orF) and use curly braces{}to contain expressions. - This feature, introduced in Python 3.6, makes string formatting much more straightforward.

Why Use f-Strings?

- Readability: The expressions are right within the string, making it easy to see what’s being formatted.

- Conciseness: Less boilerplate code compared to older formatting methods like

.format()or%. - Performance: Generally faster than other string formatting methods.

Feature Store

- Dictionaries can temporarily hold features for a single sample before passing to a model.

- This is particularly useful when working with

DictVectorizerin text processing.

from sklearn.feature_extraction import DictVectorizer

data = [{"color": "red", "size": "small"}, {"color": "blue", "size": "large"}]

vec = DictVectorizer(sparse=False)

features = vec.fit_transform(data)

print(features)

print(vec.get_feature_names_out())[[0. 1. 0. 1.]

[1. 0. 1. 0.]]

['color=blue' 'color=red' 'size=large' 'size=small']Key Takeaways

- Dictionaries provide flexible key-value storage for diverse data.

- They are crucial for organizing data, especially when converting to

pd.DataFrame. - In

sklearn, dictionaries are indispensable for hyperparameter tuning and model configuration, making your machine learning workflows more organized and reproducible.

The Dataset

MNIST

- Basically, MNIST contains:

- Handwritten digits from government forms

- What digit someone thought the person was trying to write.

- We will:

- Try to get a computer to do this work for us.

- Let’s look at an example.

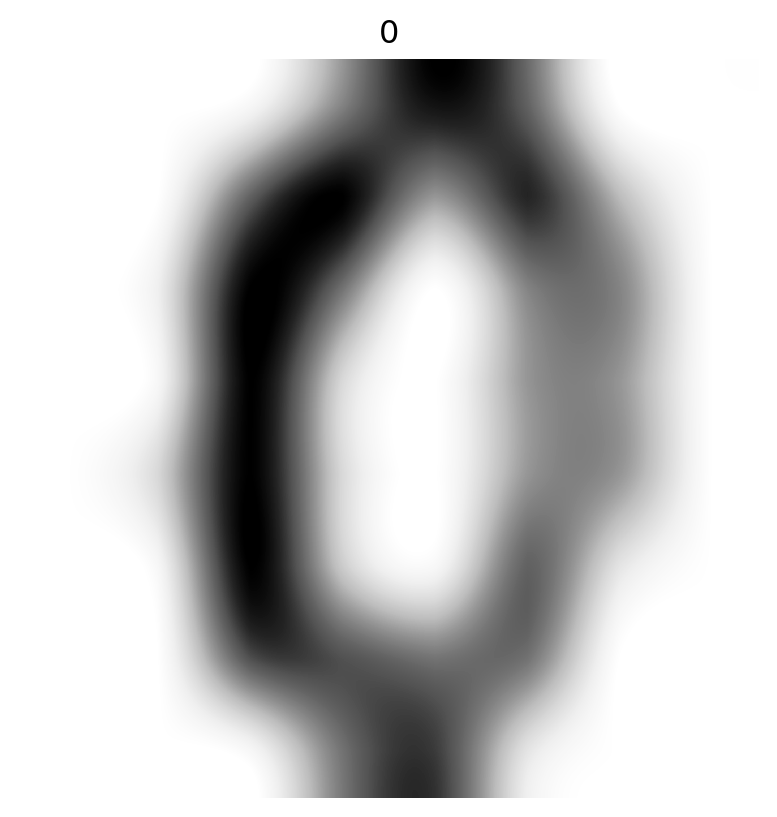

“target”

- “target” gives what a human thought the digit was.

- It is generally regard that whoever set the targets was mostly correct.

- The first ten digits are thought to be:

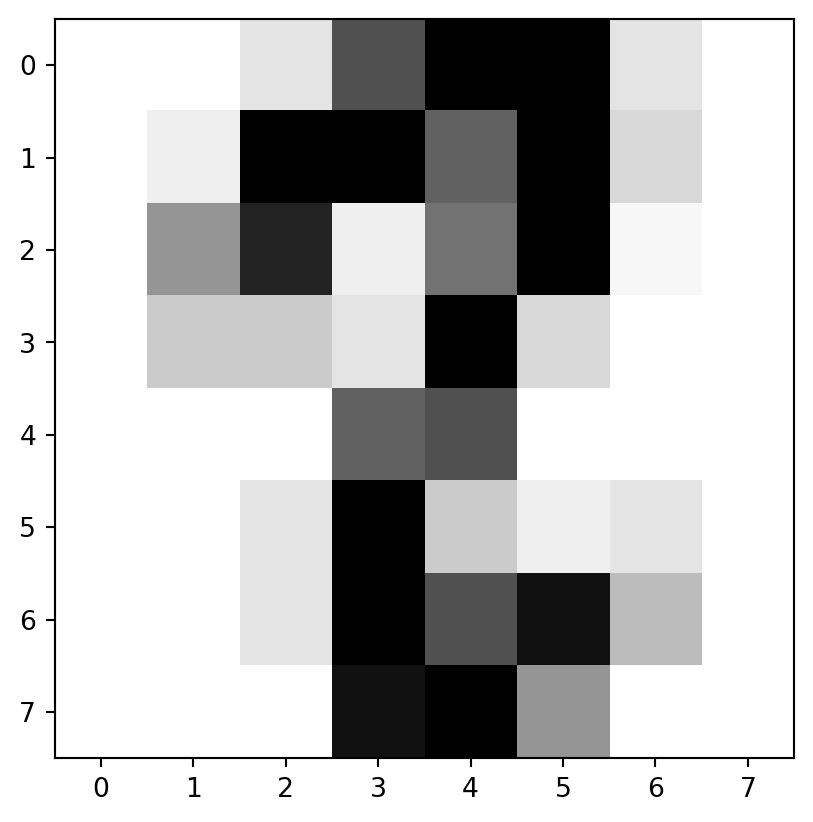

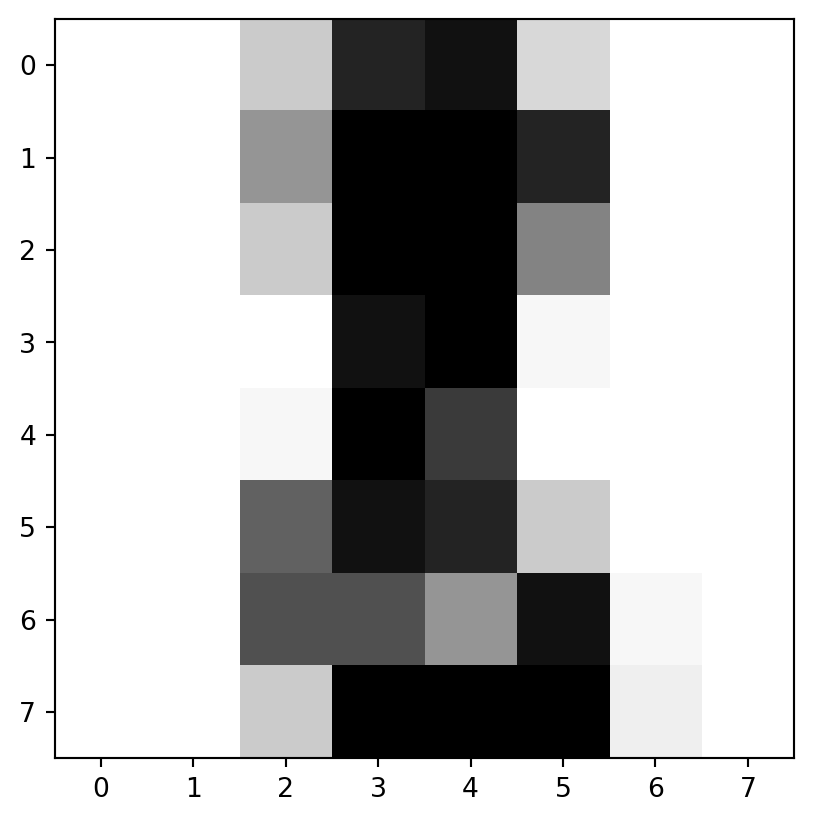

“images”

- “images” are more complicated.

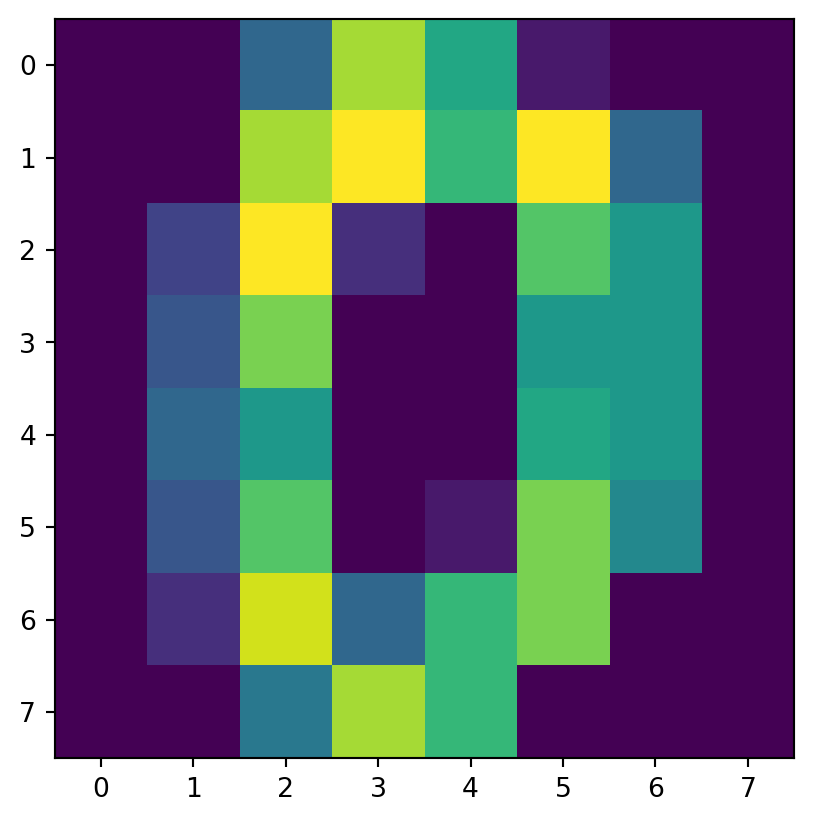

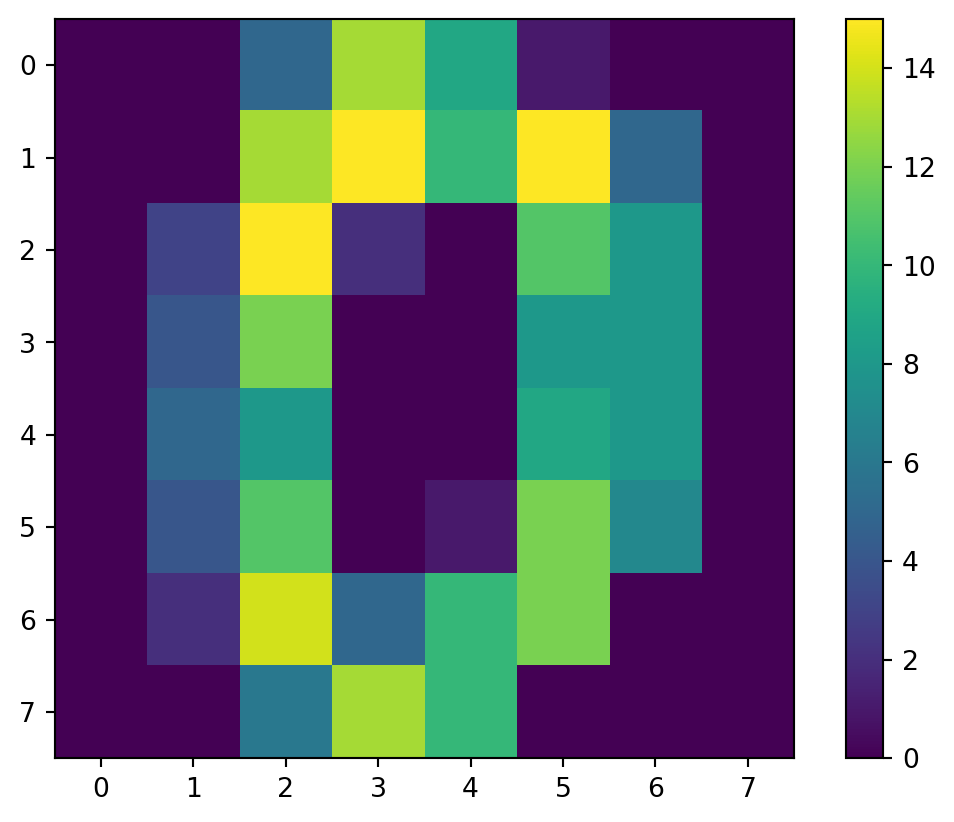

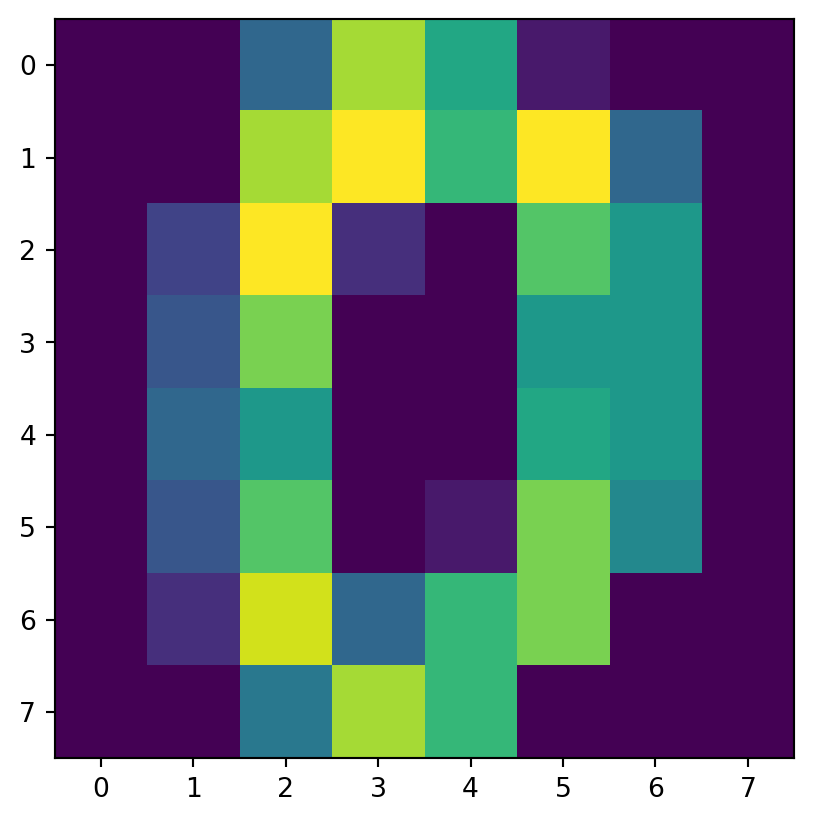

- Let’s take a look at just the initial image:

array([[ 0., 0., 5., 13., 9., 1., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 13., 15., 10., 15., 5., 0.],

[ 0., 3., 15., 2., 0., 11., 8., 0.],

[ 0., 4., 12., 0., 0., 8., 8., 0.],

[ 0., 5., 8., 0., 0., 9., 8., 0.],

[ 0., 4., 11., 0., 1., 12., 7., 0.],

[ 0., 2., 14., 5., 10., 12., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 6., 13., 10., 0., 0., 0.]])Examine

Takeways

imis an 8-by-8 array of values from 0 to 16

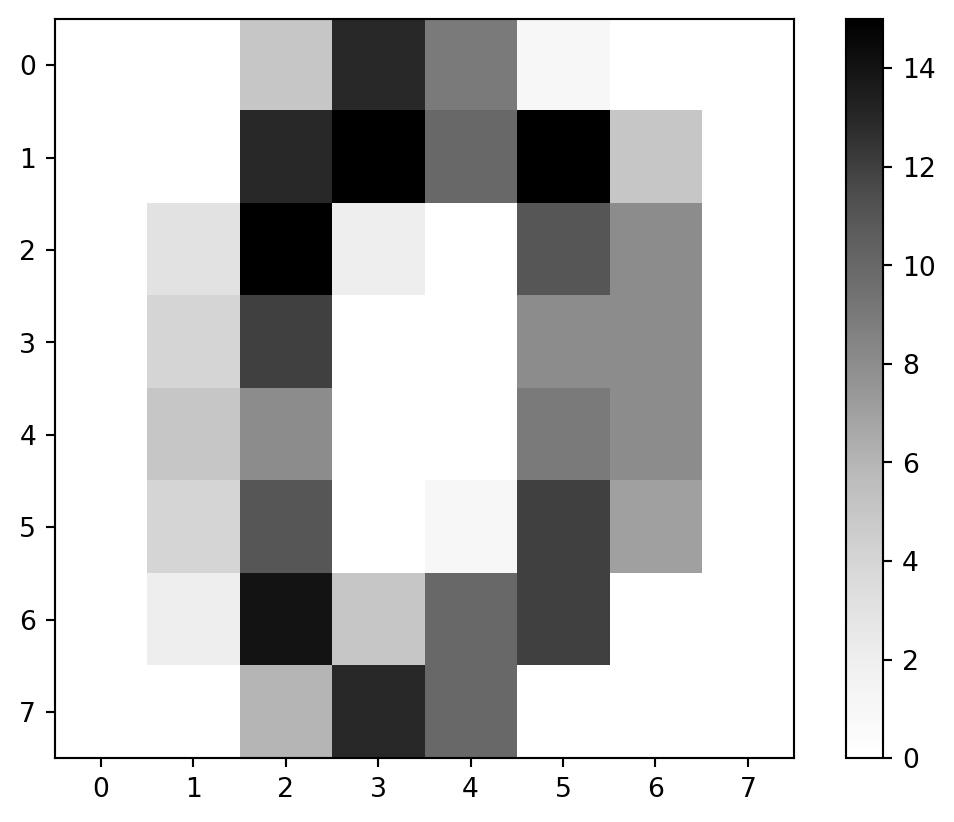

Coloration

- Might be easier in grayscale.

cmap

- Matplotlib provides colormaps we can specify.

- I say a

'Greys'in there.

- I say a

Greyscale

Interpolation

- Use an interpolater (

'spline16'looked good).

It’s a zero

Look at more

- Write a function to check some images out.

- Wait how many do I have?

See More

Classification

Classification

Flatten

- We, as humans, recognize that those things look a lot like images.

- But the images are 3D array, which is more more annoying to work with than one-row-per-digit.

- To begin, we “flatten” to 2D images into 1D arrays.

- We want

1794arrays of length64(was: 8-by-8)

Reshape

- We use NumPy

.reshape

array([[ 0., 0., 5., 13., 9., 1., 0., 0., 0., 0., 13., 15., 10.,

15., 5., 0., 0., 3., 15., 2., 0., 11., 8., 0., 0., 4.,

12., 0., 0., 8., 8., 0., 0., 5., 8., 0., 0., 9., 8.,

0., 0., 4., 11., 0., 1., 12., 7., 0., 0., 2., 14., 5.,

10., 12., 0., 0., 0., 0., 6., 13., 10., 0., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 0., 12., 13., 5., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 11., 16.,

9., 0., 0., 0., 0., 3., 15., 16., 6., 0., 0., 0., 7.,

15., 16., 16., 2., 0., 0., 0., 0., 1., 16., 16., 3., 0.,

0., 0., 0., 1., 16., 16., 6., 0., 0., 0., 0., 1., 16.,

16., 6., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 11., 16., 10., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 0., 4., 15., 12., 0., 0., 0., 0., 3., 16., 15.,

14., 0., 0., 0., 0., 8., 13., 8., 16., 0., 0., 0., 0.,

1., 6., 15., 11., 0., 0., 0., 1., 8., 13., 15., 1., 0.,

0., 0., 9., 16., 16., 5., 0., 0., 0., 0., 3., 13., 16.,

16., 11., 5., 0., 0., 0., 0., 3., 11., 16., 9., 0.]])Models

- Foundation to the notion of machine learning is training and testing.

- More properly to supervised machine learning, but more on that latter.

- Specifically, using training data, we will set the coefficients and parameters of a model, which we can think of as a function with a number of parameters.

Splits

- We split up our data, and

- Some data we use to train a model.

- Basically, find coefficients of a function.

- Some data we use to test a classifier

- Compare model to actual.

- Some data we use to train a model.

Supervised Learning

Train-Test Split

- The training set is used to teach our model to identify patterns and relationships.

- The testing set is held-out to evaluate the trained model on new, unseen data.

Supervised Learning

- Supervised learning is a type of machine learning where the algorithm learns from labeled data.

- Labeled data consists of input features (

X) and corresponding outcomes (y).

Models and Coefficients

- A model represents the learned relationship inputs-to-targets

- Sometimes this relationship is expressed through coefficients.

- Change in the target a unit change in input feature with other features constant.

Higher Dimensions

- With multiple input features, each has a coefficient.

- The sign and magnitude of each coefficient show the influence of a feature.

d = {'size': [1000, 1500, 1200, 1800], 'bedrooms': [2, 3, 2, 4], 'price': [200, 300, 240, 360]}

df = pd.DataFrame(d)

X_train, y_train = df[['size', 'bedrooms']], df['price']

model = LinearRegression()

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

model.coef_, model.intercept_(array([ 2.00000000e-01, -1.32379986e-14]), np.float64(0.0))The Digits

- We can train/test split the digits like so:

Classifiers

Perceptron

- We use a perceptron, one of the oldest and most famous machine learning frameworks.

The artificial neuron network was invented in 1943 by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts in A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity.

- Described visually in textbooks in 1958

- Inspired by neuroscience ideas of the time.

Import

- Import and create a perceptron.

from sklearn.linear_model import Perceptron

clf = Perceptron() # This will be the model that will contain coefficients

clf # At first, not fitted to anything!Perceptron()In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

Perceptron()

Training

- We train or

.fit()the model to the data.

Perceptron()In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

Perceptron()

- Then we can predict over the testing set!

Not bad!

- More detailed reporting from

metrics

from sklearn import metrics

# We print so it looks a bit nicer

print(metrics.classification_report(y_test, y_pred)) precision recall f1-score support

0 0.98 0.98 0.98 44

1 0.83 0.98 0.90 44

2 1.00 0.95 0.97 39

3 0.98 0.95 0.97 44

4 1.00 0.95 0.97 38

5 0.96 1.00 0.98 51

6 1.00 0.98 0.99 48

7 1.00 1.00 1.00 37

8 0.84 0.92 0.88 63

9 0.97 0.74 0.84 42

accuracy 0.94 450

macro avg 0.96 0.94 0.95 450

weighted avg 0.95 0.94 0.94 450

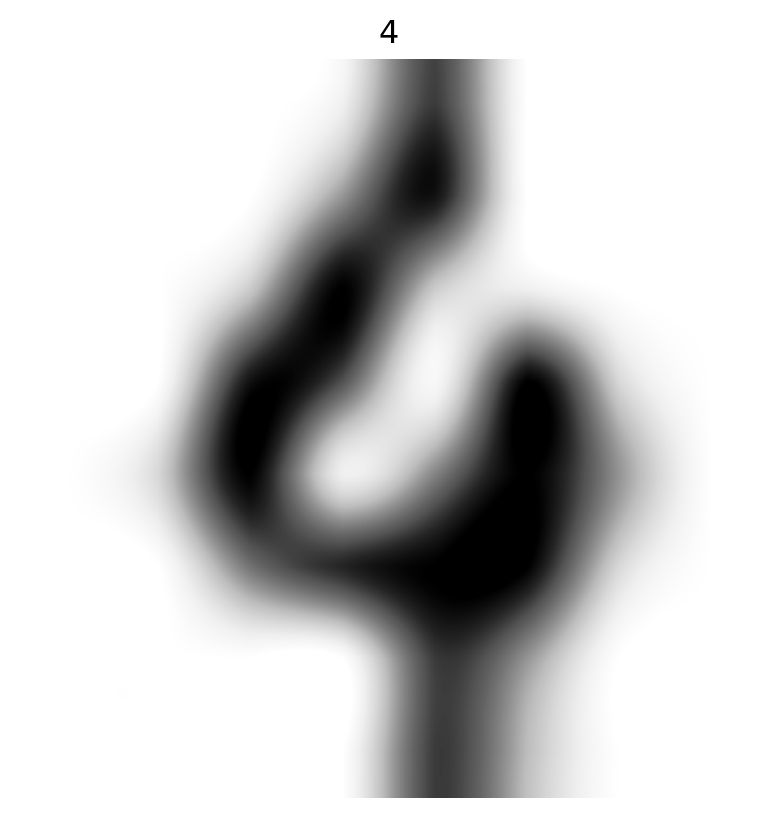

Where did we miss?

- We can see what we got wrong.

array([ 4, 8, 35, 36, 45, 56, 63, 67, 113, 158, 184, 191, 198,

199, 204, 273, 305, 316, 326, 352, 360, 366, 415, 437, 444])- Let’s look at the first two of those.

Two Misses

On Accuracy

- Machine learning frameworks were doing better than I could do around ~2010

- On these older datasets with:

- Greyscale

- 16 color

- 64 pixel

- Maybe your eyes are better than the perceptron, but mine aren’t!

Clustering

Unsupervised Learning

- Unsupervised learning deals with unlabeled data, where there are no predefined target variables (

y). - Find hidden patterns, structures, or relationships within the data itself.

Clustering

- Clustering is an unsupervised learning task that groups data points into clusters based on their similarity.

- Data points within the same cluster are more similar to each other than to those in other clusters.

- The goal is to discover natural groupings in the data without any prior knowledge of those groups.

\(k\)-means Clustering

- \(k\)-means clustering is a popular partitioning algorithm that divides data into

kpredefined clusters. - It aims to minimize the sum of squared distances between data points and their assigned cluster’s centroid.

- The

kparameter (number of clusters) must be specified in advance.

How \(k\)-means Works

- Start: \(k\) data points as cluster centroids.

- Assign: To the cluster with closest center.

- Update: Recalculate the cluster mean.

- Repeat: Until the assignments no longer change.

Interpreting \(k\)-means Results

- After fitting, \(k\)-means provides cluster labels for each data point and the coordinates of the cluster centroids.

- The labels indicate which cluster each data point belongs to.

- The centroids represent the “center” of each cluster.

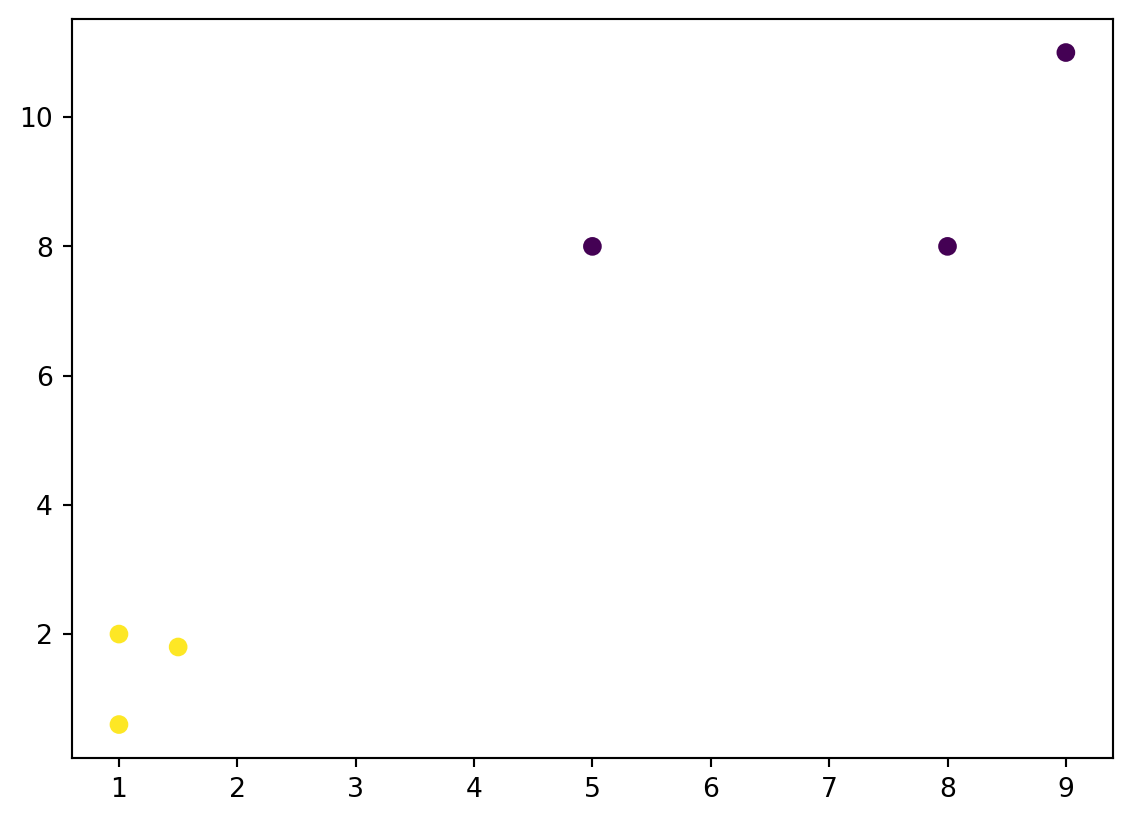

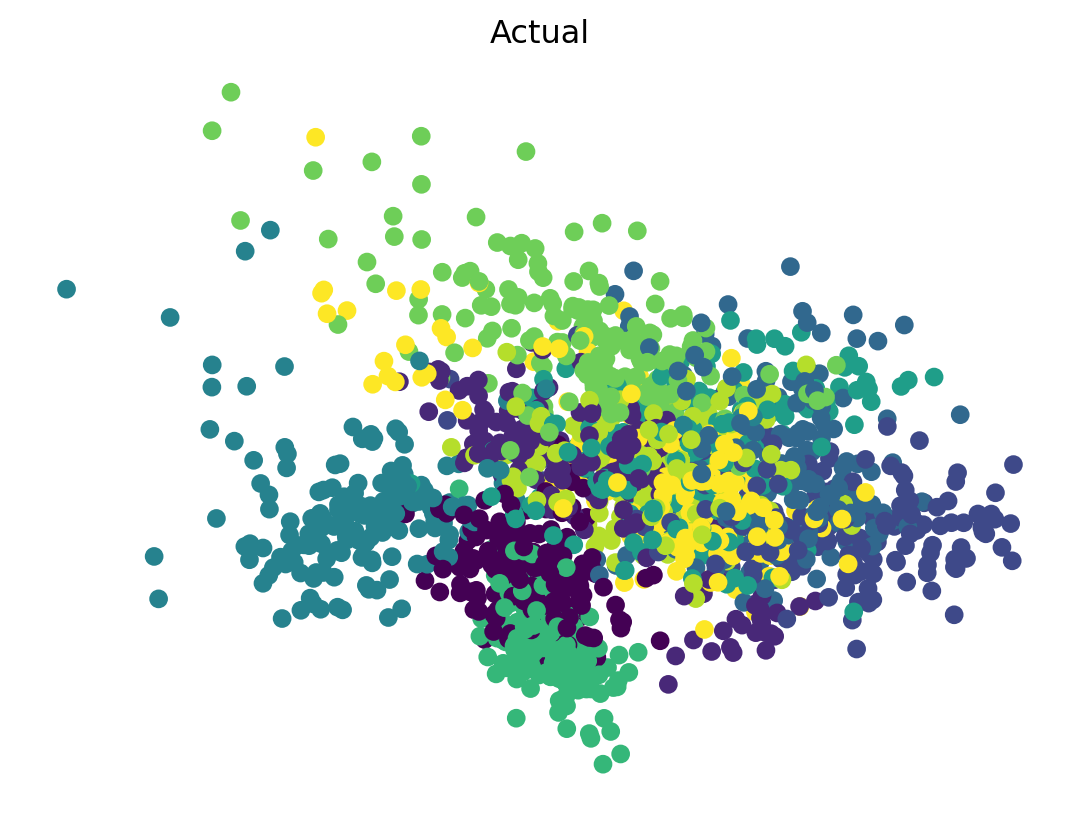

Plot it

Choosing \(k\)

- Determining the optimal

kis a common challenge in \(k\)-means. - The choice of

koften depends on domain knowledge and the goal of the clustering. - We “cheat” on the digits set - there are 10 digits (exact)

Exercise

Cluster Digits

- For the exercise we will cluster the digits.

- We will use Principle Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce from 64 to fewer dimensions.

Principal Component Analysis

- Dimensionality reduction technique.

- Transforms high-dimensional data into fewer, uncorrelated principal components.

- Components capture maximum data variance.

PCA: Explained Variance

- Each principal component captures a proportion of the total variance (explained variance ratio).

- Helps decide how many components to keep.

Code Sample

(array([[0.39250186, 0.86027584, 0.0088714 , 0.09031264, 0.92406155],

[0.02823733, 0.66593355, 0.91355326, 0.38840791, 0.86576046],

[0.13334149, 0.67490569, 0.47429288, 0.74461236, 0.62912872],

[0.45579094, 0.29786937, 0.85740943, 0.08848002, 0.78133508],

[0.07463008, 0.96488199, 0.27140834, 0.93849056, 0.72967892]]),

array([-0.80350742, -1.76749167]))Benefits of PCA

- Simplifies data and reduces storage.

- Can reduce noise.

- Useful for visualization.

- Important: Data scaling is crucial.

StandardScaler().fit_transform()

Exercise

- Use PCA and \(k\)-means on the digit data.

- You may need to try different PCA numbers.

- Look at a 2+ examples in 2+ clusters.

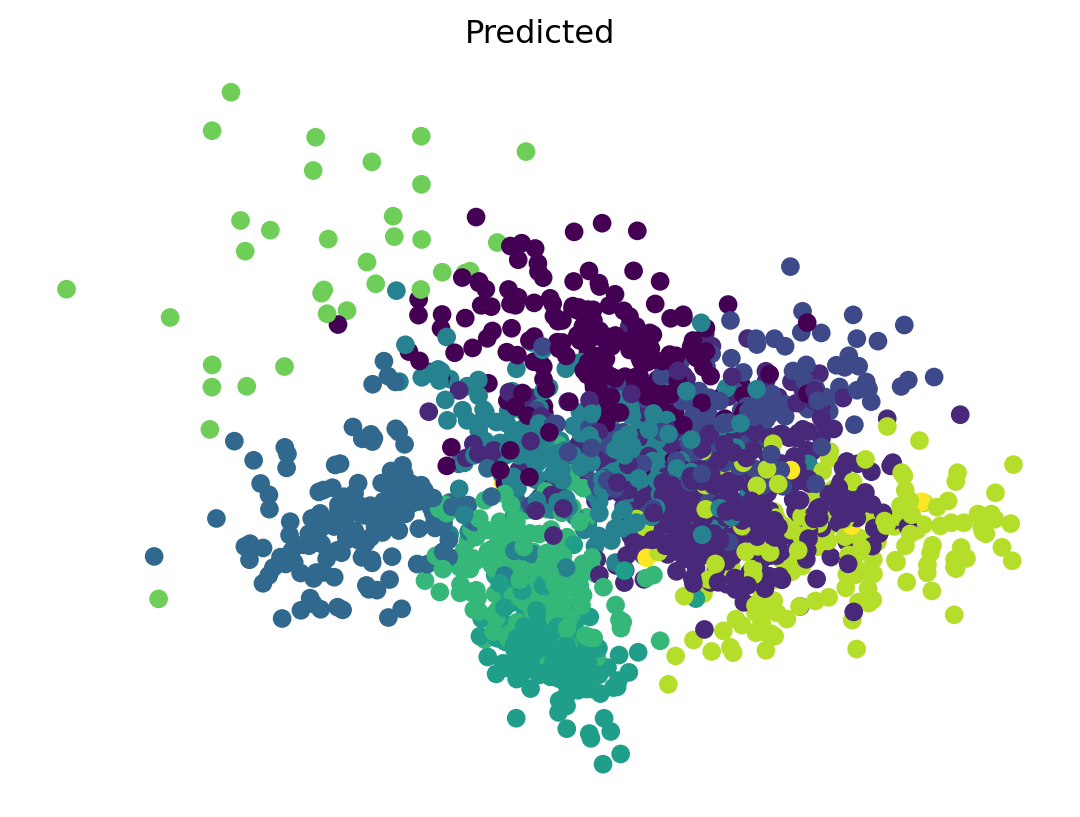

- Plot the classification.

- I’ll use PCA with 2 dimensions for

xandy - Two plots, colored for actual and predicted.

- I’ll use PCA with 2 dimensions for

Solution

- \(k\)-means

Looker

- I wrote a function to look at things.